Women Comming From Domstic Viloent Siuoations Act When Dating Again

Intimate partner violence in Canada, 2018: An overview

by Adam Cotter, Canadian Middle for Justice and Community Safety Statistics

Release date: April 26, 2021

Intimate partner violence (IPV) encompasses a broad range of behaviours, ranging from emotional and fiscal corruption to physical and sexual assault. Due to its widespread prevalence and its far-ranging firsthand and long-term consequences for victims, Annotation their families, and for communities as a whole, IPV is considered a major public health trouble (World Health System 2017). In addition to the straight impacts on victims, IPV also has broader economical consequences (Peterson et al. 2018) and has been linked to the perpetuation of a bicycle of intergenerational violence, leading to additional trauma.

Many victimization surveys in Canada and elsewhere prove that the overall prevalence of self-reported IPV is similar when comparing women and men. That said, looking beyond a high-level overall measure out is valuable and can reveal important context and details nearly IPV. An overall measure oftentimes encompasses multiple types of IPV, including one-fourth dimension experiences and patterns of abusive behaviour. These differences in patterns and contexts help to underscore the indicate that in that location is not ane singular experience of IPV. Rather, different types of intimate partner victimization—and different profiles among diverse populations—exist and are important to acknowledge as they will call for different types of interventions, programs, and supports for victims.

Research to date has shown that women disproportionately experience the most severe forms of IPV (Burczycka 2016; Breiding et al. 2014), such every bit being choked, beingness assaulted or threatened with a weapon, or being sexually assaulted. Additionally, women are more likely to experience more than frequent instances of violence and more ofttimes report injury and negative physical and emotional consequences every bit a issue of the violence (Burczycka 2016). Though most instances of IPV practice non come to the attention of police, women incorporate the majority of victims in cases that are reported (Conroy 2021). Furthermore, homicide data have consistently shown that women victims of homicide in Canada are more than likely to be killed by an intimate partner than by whatever other blazon of perpetrator (Roy and Marcellus 2019). Amid solved homicides in 2019, 47% of women who were victims of homicides were killed by an intimate partner, compared with six% of homicide victims who were men.

This article, focusing on the overall Canadian population, is ane in a series of brusk reports examining experiences of intimate partner violence among members of different population groups, based on self-reported data from the 2018 Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS) for various populations. Information technology explores the prevalence, nature, and impact of IPV on Canadians taking a gender-based arroyo by comparing the experiences of women and men. Note Experiences of IPV amongst Ethnic women (Heidinger 2021), sexual minority women (Jaffray 2021a) and men (Jaffray 2021b), women with disabilities (Savage 2021a), young women (Barbarous 2021b), and visible minority women (Cotter 2021) are examined in the other reports within this series. Note

In this article, the term "intimate partner violence" is used to refer to all forms of violence committed in the context of an intimate partner relationship (see Text box 1). Other organizations may prefer other terms, or use them interchangeably with intimate partner violence, such as spousal violence, dating violence, or domestic violence. However, these terms can exclude certain types of intimate partner violence by limiting the telescopic to a item blazon of intimate partner human relationship, or could encompass other types of violence which take identify in another type of relationship but within the domestic context, such as kid abuse or elder abuse (World Health Organization 2012).

Start of text box i

Text box 1

Measuring and defining intimate partner violence

The Survey of Safe in Public and Individual Spaces (SSPPS) collected information on Canadians' experiences of intimate partner violence (IPV) since the age of 15 and in the 12 months that preceded the survey. The survey used a wide range of items covering abusive and vehement behaviours committed past intimate partners, including psychological, physical, and sexual violence. The definition of partner was also wide and included current and former legally married spouses, common-constabulary partners, dating partners, and other intimate partner relationships.

The 27 items used in the SSPPS were drawn from various sources, including the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS), the Composite Abuse Scale Revised Brusk Form (CASr-SF) (Ford-Gilboe et al. 2016), and new items designed to address gaps in both of these measures (come across Tabular array 1A for a complete list of all items included in the survey, as well as their source). Including a wide range of IPV types was disquisitional to ensuring that all forms of violence were captured in order to reflect the experiences of various individuals and populations. This includes experiences of IPV in relationships involving partners of the aforementioned or of a different gender, every bit well as specific experiences of IPV amidst men and women.

Defining and counting intimate partner violence

Intimate partner violence can exist divers in a number of ways, and the definition tin evolve over time to include emerging forms of IPV. For case, Statistics Canada defines police-reported intimate partner violence as violent offences that occur between current and quondam partners who may or may not live together (Burczycka 2018). The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (2019) defines IPV as, broadly, harm caused by an intimate partner, which takes many forms but is often the result of an attempt to proceeds or assert ability or command over a partner.

In the SSPPS, intimate partner violence is defined equally any act or behaviour committed by a electric current or old intimate partner, regardless of whether or non these partners lived together. In this article, intimate partner violence is broadly categorized into three types: psychological violence, physical violence, and sexual violence.

Psychological violence encompasses forms of abuse that target a person'due south emotional, mental, or financial well-being, or impede their personal freedom or sense of safe. This category includes 15 specific types of abuse, including jealousy, proper name-calling and other put-downs, stalking or harassing behaviours, manipulation, confinement, or property harm (for a complete list of items included in this category, run across Table 1A). Information technology also includes being blamed for causing the abusive or fierce behaviour, which was measured among those respondents who experienced certain forms of IPV. Notation

Physical violence includes forms of abuse that involve physical assault or the threat of concrete assault. In all, nine types of abuse are included in this category, including items being thrown at the victim, being threatened with a weapon, being slapped, being beaten, and existence choked (meet Table 1A).

Sexual violence includes sexual attack or threats of sexual assault and was measured using two items from the CASr-SF: being fabricated to perform sex acts that the victim did not desire to perform, and forcing or attempting to forcefulness the victim to have sex activity.

Physical and sexual intimate partner violence are sometimes collapsed into one category, particularly when data on IPV are combined with not-IPV data in club to derive a total prevalence of criminal victimization.

Frequency of intimate partner violence

In addition to measuring the prevalence of intimate partner violence, the SSPPS also measured the frequency of each form of intimate partner violence in the past 12 months. Respondents who stated that they had experienced whatever of the 27 forms of abuse were asked to specify the frequency of that corruption—that is, if the abuse had happened in one case, a few times, monthly, weekly, or daily or about daily within the past 12 months. This information provides additional context and nuance in highlighting the experiences of victims and when making comparisons between different populations.

Analytical approach

The analysis presented in this article takes an inclusive approach to the broad range of behaviours that comprise IPV. For the purposes of this analysis, those with at least i response of 'yes' to any particular on the survey measuring IPV are included as having experienced intimate partner violence, regardless of the type or the frequency.

IPV data from other sources

While this analysis relies on data from the SSPPS, in that location are other sources of national information on IPV in Canada. Most notably, the Full general Social Survey on Victimization (GSS) has collected information on intimate partner violence using the Disharmonize Tactics Scale (CTS) every 5 years since 1999, with data for 2019 available in 2021. Dissimilar the SSPPS, the GSS focused on the past 5-twelvemonth and past 12-month occurrence of emotional, concrete, and sexual violence committed by a electric current or former legally married or common-police spouse or partner. In 2014, dating violence was captured through the addition of a brief module, which was expanded to align with the CTS in 2019.

The reward of the GSS is that information technology allows for analysis of this blazon of intimate partner violence over fourth dimension, also equally greater international comparability. On the other hand, the SSPPS includes a broader telescopic of abusive behaviours and potential abusive relationships, and the key power to provide a measure of lifetime prevalence and a measure of frequency of all types of behaviour, beyond those that are physically or sexually violent. IPV data from the GSS will exist published in futurity Juristat articles.

Information on IPV are also collected in the Uniform Law-breaking Reporting Survey (UCR). The UCR includes details on the incidents, defendant, and victims, but is express but to those incidents that come to the attention of police. For the most contempo UCR IPV data, see Conroy (2021).

End of text box i

More than than iv in x women and ane-3rd of men have experienced some course of IPV in their lifetime

While physical and sexual assault are the most overt forms of intimate partner violence (IPV), they are not the but forms of violence that be in intimate partner relationships. IPV as well includes a variety of behaviours that may not involve physical or sexual violence or rise to the current level of criminality in Canada, merely nevertheless crusade victims to feel afraid, anxious, controlled, or cause other negative consequences for victims, their friends, and their families.

On the whole, experiences of IPV are relatively widespread amongst both women and men. Overall, 44% of women who had e'er been in an intimate partner relationship—or about six.two one thousand thousand women 15 years of age and older—reported experiencing some kind of psychological, physical, or sexual violence in the context of an intimate relationship in their lifetime (since the historic period of 15 Notation ) (Tabular array 1A, Table 2). Annotation Amongst always-partnered Annotation men, iv.9 million reported experiencing IPV in their lifetime, representing 36% of men. Note

By far, psychological abuse was the near common blazon of IPV, reported by about four in ten ever-partnered women (43%) and men (35%) (Table 1A, Table 2). This was followed by physical violence (23% of women versus 17% of men) and sexual violence (12% of women versus 2% of men). Notably, nearly 6 in ten (58%) women and virtually half (47%) of men who experienced psychological corruption too experienced at least one form of concrete or sexual abuse. Regardless of the category being measured, significantly higher proportions of women than men had experienced violence.

In addition to having a college overall likelihood of experiencing psychological, concrete and sexual IPV than men, women who were victimized were also more probable to have experienced multiple specific abusive behaviours in their lifetime. Nearly one in 3 (29%) women who were victims of IPV had experienced 10 or more of the calumniating behaviours measured by the survey, well-nigh twice the proportion than amongst men who were victims (16%). In contrast, men who were victims were more likely to have experienced 1, 2, or three abusive behaviours (53%), compared with 38% of women.

Most forms of intimate partner violence more prevalent amid women

Amongst women who experienced IPV, the most common abusive behaviours were being put down or chosen names (31%), being prevented from talking to others past their partner (29%), being told they were crazy, stupid, or not practiced enough (27%), having their partner need to know where they were and who they were with at all times (nineteen%), or being shaken, grabbed, pushed, or thrown (17%) (Tabular array 1A).

Four of these five—existence prevented from talking to others (27%), being put down (xix%), being told they were crazy, stupid, or not good enough (16%), and having their partner demand to know their whereabouts (15%)—were also the almost common types of IPV experienced past men. However, the prevalence among women was college for each of these abusive behaviours, as it was for most all IPV behaviours measured by the survey.

Of the 27 private IPV behaviours measured past the survey, all but two were more prevalent among women than men. Of the two exceptions, one was being slapped (reported by xi% of both women and men, but was the 5th most mutual blazon of IPV among men). The other was an item asked simply of those who reported a minority sexual identity (lesbian, gay, bisexual, or some other sexual orientation that was non heterosexual): having a partner reveal, or threaten to reveal, their sexual orientation or relationship to anyone who they did not want to know this information. This was reported by 6% of sexual minority men and vii% of sexual minority women, a difference that was non statistically meaning.

There were several types of IPV behaviour that were more than five times more prevalent among women than amongst men. These forms of violence tended to exist the less common but more severe acts measured by the survey. Women, relative to men, were considerably more probable to take experienced the following calumniating behaviours in their lifetime: being made to perform sex acts they did not desire to perform (8% versus 1%), existence confined or locked in a room or other space (iii% versus 0.5%), being forced to have sex (10% versus 2%), being choked (7% versus ane%), and having damage or threats of harm directed towards their pets (4% versus 0.8%).

Near seven in ten women and men experienced IPV by one partner

Though their overall prevalence of IPV differed, women and men reported similar numbers of abusive partners in their lifetimes, with most indicating that i intimate partner was responsible for the abuse they had experienced. This was the case for 68% of women and 69% of men who experienced IPV.

A smaller proportion of victims reported having multiple abusive partners. I in five (22%) women said they had had two abusive partners since the historic period of 15, while fewer reported iii (6%), four (1%), or five or more (1%) abusive partners. These proportions did not differ from those reported by men who experienced IPV (xx%, 4%, one%, and one%, respectively).

Women more than likely to experience fear, feet, and feelings of being controlled or trapped past a partner

Measures of intimate partner violence often accept into account the levels of fear victims experience. Beingness afraid of a partner can signal that experiences of violence are more coercive, relatively more than severe, and more probable to reflect a pattern of behaviour past an calumniating partner (Johnson and Leone 2005). This understanding of patterns and impacts of IPV underlie legislative projects that have been undertaken; for example, in 2015, the United kingdom introduced the criminal offence of "coercive control", designed to criminalize forms of abuse that may not, on their ain, constitute criminal behaviour, simply occur on a repeated or continuous basis and crusade the victim to fear for their prophylactic from violence or upshot in substantial adverse effects (Home Office 2015). Note In Canada, meanwhile, a 2021 amendment to the Divorce Act introduced definitions of family violence to the legislation, including a specific mention of coercive and controlling behaviours, which may include specific acts that are not criminal simply is a pattern of abusive behaviours designed to control or boss another (Department of Justice 2021).

Fearfulness is considerably more mutual among women who experience IPV; nearly four in 10 (37%) women who were IPV victims said that they were afraid of a partner at some point in their life because of their experiences, well above the proportion of men (9%).

Notably, the blazon of IPV experienced is associated with the likelihood of experiencing fear. Amid victims of IPV who experienced solely psychological forms of abuse, 12% of women and 4% of men stated that they had ever been afraid of a partner. In contrast, 55% of women who experienced physical or sexual IPV feared a partner at some point, as did fourteen% of men.

Beyond the wide categories, looking at the volume of dissimilar calumniating behaviors an individual experiences suggests that those who experience multiple types of violence experience greater levels of fear. For example, those who experienced the largest range of IPV behaviours were considerably more than likely to have ever feared a partner. Of women who had experienced one type of IPV since historic period 15, 4% had been afraid of a partner at some betoken. This increased to x% and 15% amid those who experienced 2 or iii behaviours, respectively, ultimately reaching 74% among women who experienced 10 or more types of IPV. Though far fewer men ever feared their partner, the blueprint was similar every bit 2% of men who experienced i blazon of IPV reported fearing a partner at some point, increasing to 28% amongst men who experienced 10 or more types. These findings are especially poignant since nearly people who experienced IPV stated that the corruption had been perpetrated by 1 partner, suggesting that many individuals—particularly women—are subject to a wide range of abusive, controlling, and trigger-happy behaviours committed by i partner whom they fear.

While calculation important context, fear is just one of several possible emotional and psychological impacts of IPV. Other emotional impacts of IPV were therefore included in the SSPPS to provide additional context to experiences of abuse; namely, feeling controlled or trapped past an abusive partner, or feeling anxious or on edge due to a partner'south abusive behaviour.

These emotions were more common than fear for both women and men, and the gender gap was smaller. For both women and men, feeling anxious or on edge (57% of women and 36% of men) was most common, followed by feeling controlled or trapped by an abusive partner (43% of women and 24% of men). As with feelings of fear, those who experienced a college number of different types of calumniating behaviour measured past the SSPPS reported these emotional impacts far more often.

More than than one in 10 women and men experienced IPV in the past 12 months

In addition to information on intimate partner violence that people feel over their lifetime, the SSPPS asked questions nearly partner abuse that had happened in the previous yr. In the 12 months preceding the survey, 12% of women and 11% of men were subjected to some form of IPV, proportions that were not statistically different (Table 1A, Table two). Women and men were as as likely to study experiencing psychological abuse (12% and 11%, respectively) or concrete or sexual violence (3% each). That said, while the prevalence of physical violence was similar between women (two.four%) and men (2.8%), sexual violence was about iii times more than common among women (1.2%) than men (0.4%).

Mirroring the lifetime data, the four most common types of IPV reported by women in the past 12 months were being put downwards or called names (8%), being told they were crazy, stupid, or not skilful enough (seven%), having their partner be jealous and not want them to talk to other men or women (five%), and having their partner demand to know where they were and who they were with (3%). These were as well the iv almost mutual IPV behaviours reported by men (6%, v%, 7%, and 4%, respectively).

Some forms of IPV were more frequently reported by men than women in the by 12 months, unlike what was seen in the lifetime prevalence data. In the past 12 months, men were more likely than women to take experienced their partner being jealous and preventing them from talking to others (vii% versus five%), demanding to know where they were and who they were with at all times (4% versus 3%), slapping them (i.7% versus 0.8%), or hit them with a fist or object, bitter, or kicking them (i.3% versus 0.7%).

On the other mitt, 12 of the 27 behaviours measured were college among women than men. Notably, this included both measures of sexual assault, being choked, threats to harm or kill them or someone shut to them, being harassed, and being followed or having their partner hang effectually their home or workplace.

More than 1-quarter of IPV victims experienced violence or abuse monthly or more than in the previous year—and one in ten women experienced it nigh daily

Intimate partner violence tends to happen repeatedly, instead of on a quondam basis. Nigh 1 in five people who experienced IPV in the 12 months preceding the survey said that it occurred in one case during that time. This was the case for a slightly higher proportion of men who were victims (22%) than women (17%).

Instead, amid IPV victims, 30% of women and 27% of men stated that at least one type of IPV (physical, sexual or psychological) had occurred repeatedly: either on a monthly footing or more often (Table 1B). Besides, over half of women (54%) and men (51%) who experienced IPV said that at least one specific abusive behaviour occurred "a few times" over the twelve month period—that is, more than in one case simply less than on a monthly basis. In both instances, the differences between women and men who were victims were non statistically different; however, women were twice as likely as men to take experienced at least i calumniating behaviour on a daily or almost daily basis in the past 12 months (12% versus half dozen%)—suggesting still another way in which IPV disproportionately impacts women.

In part due to relatively pocket-sized sample size, in that location were few statistically significant differences between women and men in terms of the frequency of each individual behaviour. However, when differences were present, information technology was ever the case that women were more likely than men to study a behaviour happening one time a calendar month or more, while men were more likely to written report a behaviour happening ane time in the past 12 months (Table 1B).

Even among the types of IPV that were less common, most women who were victims of IPV said that the behaviours occurred more than once in the by 12 months. For example, while ane% of all women said that an intimate partner forced or tried to strength them to accept sexual practice in the past 12 months, three-quarters (76%) of those women said that it happened more than once. Overall, one in five (20%) women who experienced sexual violence committed by an intimate partner in the past 12 months said that it happened monthly or more in the past 12 months. The frequency with which women experience this kind of IPV is especially notable, every bit these types of violence are often also considered to be the nigh severe.

Women more probable to written report emotional, physical consequences of IPV

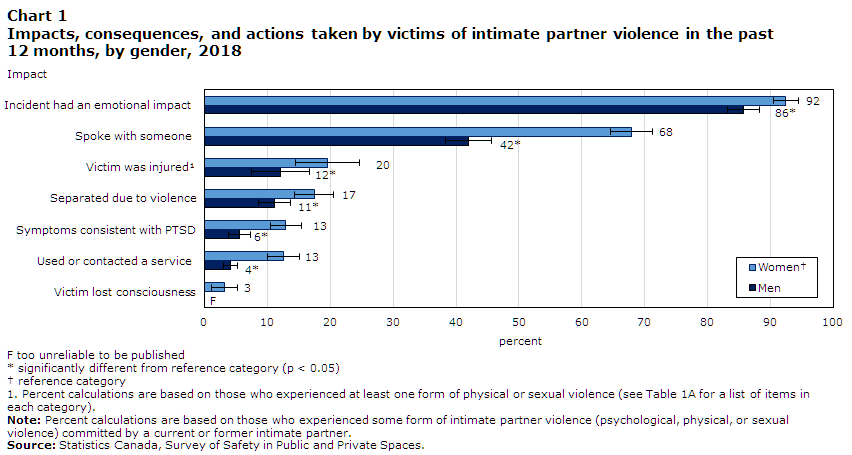

About 9 in ten victims of IPV in the past 12 months—both women (92%) and men (86%)—said that the incident had an emotional bear upon on them (Chart 1). Women, who experienced IPV more frequently and in forms that were often more severe, reported more extreme impacts on their physical and psychological health and on their fashion of life. For example, many women who were victims of IPV were injured Annotation (twenty%), separated from their partner due to the violence (17%), and had symptoms consistent with a suspicion of postal service-traumatic stress disorder Note (PTSD) (xiii%).

Nautical chart ane start

Data table for Nautical chart 1

| Bear on | Women Data tabular array for Chart 1 Notation† | Men | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percentage | standard mistake | percent | standard error | |

| Incident had an emotional bear on | 92 | 1.0 | 86 Note* | 1.3 |

| Spoke with someone | 68 | i.7 | 42 Notation* | 1.9 |

| Victim was injured Data tabular array for Chart i Note1 | 20 | two.6 | 12 Note* | 2.4 |

| Separated due to violence | 17 | 1.6 | xi Note* | i.three |

| Symptoms consistent with PTSD | 13 | 1.two | half dozen Note* | 0.9 |

| Used or contacted a service | 13 | i.three | 4 Note* | 0.5 |

| Victim lost consciousness | 3 | i.1 | NoteF: too unreliable to be published | Note...: not applicable |

| ... not applicable F too unreliable to be published

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces. | ||||

Nautical chart ane end

Notably, a considerable proportion of men who experienced IPV suffered similar consequences: 12% were injured, 11% were separated due to the violence, and 6% had symptoms consistent with PTSD.

These findings may suggest a cumulative impact of violence, as those who experienced IPV more oft tended to study greater impacts. For example, about one in xx women who experienced IPV in one case (four%) or a few times (6%) in the past 12 months reported symptoms consistent with PTSD. Amongst women who experienced IPV on a monthly footing or more, near one in 3 (30%) reported such symptoms. Similarly, one-3rd (32%) of women who experienced IPV monthly or more than were separated from their partner due to the violence, compared with about 1 in ten of those who experienced IPV in one case (nine%) or a few times (12%).

In add-on to these impacts, at that place were also some differences in the actions taken by women and men who were victims of IPV. Women were considerably more probable to take spoken with someone well-nigh the corruption or violence they experienced (68%, compared with 42% of men). Women (thirteen%) were too more likely than men (4%) to take used or contacted a victims' service because of the calumniating or violent behaviours they had experienced in the past 12 months.

The gender gap in seeking out both formal and informal supports is consistently seen in Canadian self-report surveys (Cotter and Brutal 2019; Cotter 2018; Burczycka 2016). Research suggests that many factors contribute to this pattern. For instance, gender norms surrounding masculinity can minimize men'south help-seeking behaviours in a number of contexts, not merely limited to IPV victimization (Ansara and Hindin 2010; Lysova et al. 2020). In other words, men are less likely to seek informal or formal help in the first identify—and, if they do seek out such help, there are generally fewer services for IPV victims available for men than for women (Ansara and Hindin 2010; Lysova et al. 2020).

In improver to its correlation with more than severe impacts on victims, a higher frequency of IPV was associated with greater likelihood of the violence coming to the attention of police. Women who experienced IPV on a monthly basis or more than (13%) were more than likely to say that the abuse had come to the attention of police, compared to those who had experienced IPV once (ii%) or a few times (5%). Regardless of frequency, yet, the vast majority of IPV did non come to the attending of police. This could reflect the fact that some of the IPV behaviours measured may non be perceived by victims as a criminal matter or as something that can or should be reported to law. According to the 2014 General Social Survey, the two virtually common reasons for not reporting spousal violence to the law were a conventionalities that the abuse was a individual or personal affair and a perception that information technology was not important enough to written report (Burczycka 2016).

Equally noted, the majority of IPV victims had not used or consulted a formal service in the past 12 months. The about mutual reasons given by IPV victims who did not use these services were that they didn't want or need help (51% of women and 56% of men) or that the incident was too pocket-sized (38% of women and 29% of men). A small number of victims did not employ or contact any services due to logistical issues or barriers to access—in that location were none bachelor (1% of all victims), there were none available in the victims' language (0.eight%), they were likewise far away from any services (0.5%), or there was a waiting list (0.v%). Note

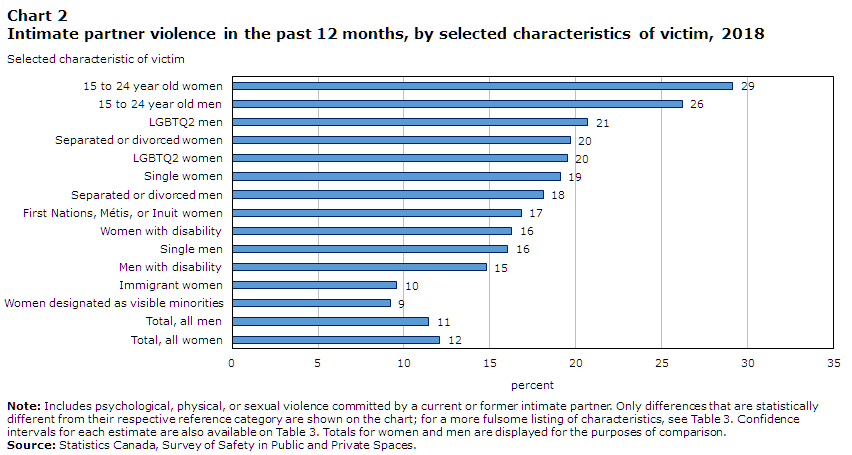

IPV much more mutual among certain populations

In addition to gender, other private and socioeconomic characteristics intersect to impact the likelihood of experiencing intimate partner violence (Table 3). For example, the prevalence of IPV was notably college among Indigenous women (see Heidinger 2021), LGBTQ2 women (run into Jaffray 2021a), LGBTQ2 men (see Jaffray 2021b), women with disabilities (Savage 2021a), and young women (encounter Fell 2021b), both since age 15 and in the past 12 months.

Victimization research has consistently shown that historic period is a major run a risk factor, with younger people being more likely to be victims of violent crime (Cotter and Savage 2019; Perreault 2015). This is as well the case with IPV. Three in x (29%) women 15 to 24 years of age reported having experienced IPV in the past 12 months, more than double the proportion found amongst women between the ages of 25 to 34 or 35 to 44, and close to six times college than that among women 65 years of age or older (Tabular array iii, Nautical chart 2). Likewise, for men, 26% of fifteen- to 24-twelvemonth-olds had experienced some class of IPV in the past 12 months, declining to five% amongst those 65 years of age and older. Research has shown that boyhood and young adulthood, when many are negotiating intimate relationships and boundaries for the first time, is a time of higher take a chance for IPV (Johnson et al. 2015). For more than information on young women who experienced IPV, see Savage (2021b).

Chart ii start

Data table for Nautical chart 2

| Selected characteristic of victim | Percent |

|---|---|

| 15 to 24 year former women | 29 |

| 15 to 24 yr old men | 26 |

| LGBTQ2 men | 21 |

| Separated or divorced women | 20 |

| LGBTQ2 women | 20 |

| Single women | 19 |

| Separated or divorced men | 18 |

| First Nations, Métis, or Inuit women | 17 |

| Women with inability | 16 |

| Unmarried men | xvi |

| Men with disability | 15 |

| Immigrant women | 10 |

| Women designated equally visible minorities | 9 |

| Full, all men | eleven |

| Total, all women | 12 |

| Note: Includes psychological, physical, or sexual violence committed by a electric current or sometime intimate partner. Simply differences that are statistically dissimilar from their respective reference category are shown on the chart; for a more fulsome listing of characteristics, see Tabular array iii. Confidence intervals for each gauge are also available on Table 3. Totals for women and men are displayed for the purposes of comparison. Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces. | |

Chart 2 end

Ethnic (Get-go Nations, Métis, and Inuit) women (61%) and men (54%) were more probable to have been victims of IPV in their lifetime compared with their non-Indigenous counterparts (44% and 36%, respectively) (Table 3). Note Indigenous women (17%) were also more likely than non-Indigenous women (12%) to take experienced IPV in the past 12 months. For more information, come across Heidinger (forthcoming 2021).

Notably, the prevalence of IPV in the by 12 months among women living in rural areas (12%) was the same equally that amongst women living in urban Canada (12%), while it was higher among men residing in urban areas (12%) compared with those in rural Canada (nine%). For rural victims of IPV, feelings of isolation or beingness trapped due to IPV may exist exacerbated further due to remoteness, lower availability of services, or problem leaving the community (Women's Shelters Canada 2020).

Lower household income associated with lifetime experiences of IPV

Lifetime experiences of IPV were more common among women (57%) and men (53%) who reported a household income of less than $20,000 in 2018 (Table three). These proportions were not significantly different from each other, but were higher than whatsoever other income group for either women or men.

There were no significant differences in the past-12 calendar month prevalence of IPV when looking at women of varying household incomes, which suggests that income itself is not necessarily a predictor of experiencing IPV. Rather, experiencing IPV in one'southward lifetime may be a factor that leads to relatively lower income later in life, as the SSPPS measured income at the time of the survey just asked nearly any incidents of IPV since the age of 15. Furthermore, for those who experience IPV, having a lower income may pose additional challenges or barriers to leaving a fierce human relationship.

IPV linked to early experiences of kid abuse

Slightly more than women (28%) than men (26%) reported that, at some signal earlier the age of 15, they were physically or sexually driveling by an adult; women were much more likely than men to have been sexually abused (12% versus 4%), while physical corruption was more common amid men (25%) than women (22%). Victimization surveys and enquiry consistently evidence that adverse babyhood experiences are associated with a higher risk of existence a victim of violence during adulthood (Burczycka 2017; Widom et al. 2008). This is especially the case with intimate partner violence; women with a history of physical or sexual abuse earlier the age of 15 were about twice every bit likely as women with no such history to take experienced IPV either since historic period 15 (67% versus 35%) or in the by 12 months (18% versus 10%).

This pattern was too axiomatic among men; over half (53%) of those who were physically or sexually abused during childhood reported experiencing IPV at some signal in their lifetime, while this was the case for three in x (30%) men who were non abused during babyhood. Also, men who were abused during childhood were more probable than those who were not to accept experienced IPV in the by 12 months (17% versus 10%).

In a similar way, emotional abuse during childhood has been shown to be associated with an increased hazard of intimate partner victimization in adulthood (Richards et al. 2017). This was also the example when it came to harsh parenting—that is, having been slapped, spanked, made to feel unwanted or unloved, or been neglected or having basic needs become unmet past parents or caregivers. Such experiences were reported by 65% of women and 62% of men, who subsequently were more likely to report IPV in their lifetime. Approximately half of women (54%) and men (45%) who experienced harsh parenting or neglect had likewise experienced IPV since age 15, compared with 25% and 21%, respectively, who did non feel harsh parenting.

Inquiry has shown that childhood experiences of violence in the abode are associated with an increased risk of violent victimization. That is, the likelihood of future perpetration of violence every bit well as victimization is increased among people exposed to violence in childhood, equally individuals may learn to expect violence equally part of an interpersonal relationship and model this behaviour in their own lives (Neppl et al. 2019; Richards et al. 2017; Widom et al. 2014). Findings from the SSPPS support this: two-thirds (64%) of women who were exposed to violence between their parents or other adults during childhood experienced violence in their own relationship at some point in their adult lives, compared with 41% of women not exposed to such violence as a child. Similarly, 59% of women who were exposed to emotional abuse between their parents or caregivers after experienced IPV, while this was the case for 32% of women who were not.

Amongst men, there was an even wider gap between those who were exposed to violence and those who were not than what was seen among women. Shut to six in ten (58%) men who were exposed to violence betwixt their parents or other adults during childhood experienced IPV in their lifetime, compared with 33% of men who were not. As well, more than one-half (53%) of men who were exposed to emotional abuse betwixt parents or caregivers reported IPV in their own relationships, a proportion that was more than double that among men who were not (25%).

Start of text box ii

Text box 2

Lifetime violent victimization

While the analysis in this report focused on violence perpetrated by intimate partners, a fulsome assay of experiences of gender-based violence also includes experiences of violence perpetrated by those other than intimate partners. This text box examines lifetime experiences of all violent victimization (physical and sexual assault) measured by the Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS), including both intimate partner violence and violence that happens in other contexts outside of intimate partner relationships.

Shut to half of women have been physically or sexually assaulted in their lifetime

Understanding experiences of vehement victimization across the life grade—both within and outside of intimate partnerships— is important when it comes to understanding the population that is affected, developing services and prevention programs, and predicting mental and physical health needs. As such, a measure of lifetime victimization was identified as a data gap to exist addressed when developing the SSPPS. Note

When combining violence committed by intimate partners and violence committed by other perpetrators, more women (45%) stated that they have been physically or sexually assaulted at to the lowest degree in one case since the age of fifteen than men (xl%) (Table 4).

One in iii women sexually assaulted in their lifetime

The overrepresentation of women equally victims of violence was largely driven by sexual assail, every bit ane-3rd (33%) of women have been sexually assaulted at some point since age xv—more than three times the proportion among men (9%) (Table iv, Nautical chart iii). Both intimate partner sexual attack (12% versus 2%) and non-intimate partner sexual assault (30% versus 8%) were notably college among women than men.

Chart 3 beginning

Data table for Nautical chart 3

| Concrete assault | Sexual assault | Total violent victimization | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||

| Women Information table for Chart 3 Annotation† | Intimate partner Data table for Chart three Note1 | 23.0 | 11.five | 25.7 |

| Non-intimate partner | 26.1 | 30.2 | 38.7 | |

| Total | 35.0 | 33.3 | 45.2 | |

| Men | Intimate partner Data table for Chart 3 Noteane | 16.5 Note* | 2.0 Notation* | 17.0 Note* |

| Not-intimate partner | 33.three Notation* | 8.2 Note* | 35.4 Note* | |

| Total | 37.9 Note* | 9.1 Note* | 39.6 Note* | |

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Condom in Public and Private Spaces. | ||||

Chart 3 terminate

In contrast, women (35%) were slightly less likely than men (38%) to accept been physically assaulted at some point since age 15. The gendered nature of this violence is notable here: while physical assail exterior of intimate partner relationships was more common for men (33%) than women (26%), concrete assault within an intimate relationship was more mutual among women (23%) than men (17%).

For women, the most common blazon of assault differed depending on the blazon of relationship. When looking at violence committed by an intimate partner, physical assault was more common than sexual assault. The reverse was truthful when looking at violence not committed by an intimate partner. For men, regardless of the relationship to the perpetrator, physical assault was far more than common than sexual assault. Similar patterns were seen in the past-12 month data (Table v).

In every province and territory, women more than likely than men to be victims of physical or sexual IPV

In each of the provinces and territories, women were more likely than men to have experienced concrete or sexual assault committed by an intimate partner since the age of fifteen (Table 6). When combining intimate partner and not-intimate partner violence, the lifetime prevalence was higher amongst women than men in Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, Quebec, Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia. In every other province and each of the territories, in that location was no significant difference in the prevalence of violent victimization since age fifteen when comparing women and men. Of note, betwixt half and 2-thirds of all women have experienced physical or sexual assault since the age of xv in Nova Scotia (49%), Alberta (50%), British Columbia (50%), Nunavut (57%), Northwest Territories (61%), and Yukon (66%).

Finish of text box 2

Detailed data tables

Table 1A Intimate partner violence, since age 15 and in the past 12 months, by type of intimate partner violence, Canada, 2018

Table 1B Frequency of violence among those who experienced intimate partner violence in the past 12 months, by type of violence and gender, Canada, 2018

Table ii Intimate partner violence, since age 15 and in the past 12 months, Canada, 2018

Table 3 Intimate partner violence, since age 15 and in the by 12 months, past selected characteristics of victim, Canada, 2018

Table 4 Physical and sexual set on committed past intimate partners and non-intimate partners since age xv, Canada, 2018

Tabular array 5 Physical and sexual assault committed by intimate partners and non-intimate partners in the past 12 months, Canada, 2018

Table vi Physical and sexual set on committed by intimate partners and non-intimate partners since age 15, by province and territory, 2018

Survey clarification

In 2018, Statistics Canada conducted the beginning bicycle of the Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS). The purpose of the survey is to collect data on Canadians' experiences in public, at piece of work, online, and in their intimate partner relationships.

The target population for the SSPPS is the Canadian population aged xv and older, living in the provinces and territories. Canadians residing in institutions are not included. This means that the survey results may non reflect the experiences of intimate partner violence amidst those living in shelters, institutions, or other collective dwellings. In one case a household was contacted, an private 15 years or older was randomly selected to respond to the survey.

In the provinces, information drove took place from April to December 2018 inclusively. Responses were obtained by self-administered online questionnaire or by interviewer-administered telephone questionnaire. Respondents were able to answer in the official language of their choice. The sample size for the 10 provinces was 43,296 respondents. The response rate in the provinces was 43.one%.

In the territories, data collection took place from July to Dec 2018 inclusively. Responses were obtained past cocky-administered online questionnaire or past interviewer-administered in-person questionnaire. Respondents were able to respond in the official language of their choice. The sample size for the three territories was 2,597 respondents. The response rate in the territories was 73.2%.

Non-respondents included people who refused to participate, could non be reached, or could not speak English or French. Respondents in the sample were weighted so that their responses stand for the non-institutionalized Canadian population aged fifteen and older.

Data limitations

Equally with any household survey, there are some data limitations. The results are based on a sample and are therefore field of study to sampling errors. Somewhat different results might accept been obtained if the entire population had been surveyed.

For the quality of estimates, the lower and upper bounds of the confidence intervals are presented. Confidence intervals should be interpreted every bit follows: If the survey were repeated many times, and then 95% of the time (or xix times out of 20), the confidence interval would comprehend the true population value.

References

Ansara, D.L. and Hindin, G.J. 2010. "Formal and informal aid-seeking associated with women's and men's experiences of intimate partner violence in Canada." Social Scientific discipline & Medicine, Vol. 70. p. 1011-1018.

Breiding, One thousand.J., Chen J., and Black, Thou.C. 2014. Intimate Partner Violence in the United States — 2010. Atlanta, GA National Center for Injury Prevention and Command, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Burczycka, M. 2019. "Police force-reported intimate partner violence in Canada, 2018." In Family unit violence in Canada: A statistical contour, 2018. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Burczycka, M. 2017. "Profile of Canadian adults who experienced childhood maltreatment." In Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2015. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-Ten.

Burczycka, G. 2016. "Trends in self-reported spousal violence in Canada, 2014." In Family violence in Canada: A statistical contour, 2014. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-10.

Conroy, S. 2021. Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2019. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Cotter, A. 2021. "Intimate partner violence: Experiences of visible minority women in Canada, 2018." Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Cotter, A. and Savage, L. 2019. "Gender-based violence and inappropriate sexual behaviour in Canada, 2018: Initial findings from the Survey of Prophylactic in Public and Individual Spaces." Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Cotter, A. 2018. "Violent victimization of women with disabilities in Canada, 2014." Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Department of Justice Canada. 2021. Divorce and Family Violence . (accessed one March 2021).

Ford-Gilboe, M., Wathen, C.N., Varcoe, C., MacMillan, H.L., Scott-Storey, K., Mantler, T., Hegarty, K. and N. Perrin. 2016. "Development of a brief measure of intimate partner violence experiences: The Blended Abuse Calibration (Revised)—Short Form (CASR-SF)." BMJ Open. Vol. 6, no. 12.

Heidinger, L. 2021. "Intimate partner violence: Experiences of Commencement Nations, Métis, and Inuit women in Canada, 2018." Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Home Office. 2015. Decision-making or Coercive Behaviour in an Intimate or Family Relationship—Statutory Guidance Framework. (accessed 25 February 2021).

Jaffray, B. 2020. "Experiences of violent victimization and unwanted sexual behaviours amidst gay, lesbian, bisexual and other sexual minority people, and the transgender population, in Canada, 2018". Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-10.

Jaffray, B. 2021a. "Intimate partner violence: Experiences of sexual minority women in Canada, 2018." Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Jaffray, B. 2021b. "Intimate partner violence: Experiences of sexual minority men in Canada, 2018." Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-10.

Johnson, M.P. and Leone, J.K. 2005. "The differential effects of intimate terrorism and situational couple violence: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey." Journal of Family Issues. Vol. 26, no. iii. p. 322‑349.

Johnson, W.L., Manning, W.D., Giordano, P.C. and One thousand.A. Longmore. 2015. "Relationship context and intimate partner violence from adolescence to young adulthood." Journal of Adolescent Health. Vol. 57, no. 6. p. 631-636.

Lysova, A., Hanson, Thou., Dixon, Fifty., Douglas, E. M., Hines, D. A., and E.One thousand. Celi. 2020. "Internal and external barriers to assistance seeking: Voices of men who experienced abuse in the intimate relationships." International Periodical of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. Advance online publication.

Neppl, T.Yard., Lohman, B.J., Senia, J.M., Kavanaugh, S.A., and M. Cui. 2019. "Intergenerational continuity of psychological violence: Intimate partner relationships and harsh parenting." Psychology of Violence. Vol. nine, no. three. p. 298-307.

Perreault, S. 2015. "Criminal victimization in Canada, 2014." Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Perreault, S. 2020a. "Gender-based violence: Unwanted sexual behaviours in Canada'south territories, 2018." Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-10.

Perreault, S. 2020b. "Gender-based violence: Sexual and concrete attack in Canada's territories, 2018." Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Peterson, C., Kearns, K.C., McIntosh, West.L., Estefan, L.F., Nicolaidis, C., McCollister, One thousand.E., Gordon, A., and C. Florence. 2018. "Lifetime economic burden of intimate partner violence among U.S. adults." American Journal of Preventative Medicine. Vol. 55, no. 4. p. 433-444.

Richards, T.N., Tillyer, M.South. and E.G. Wright. 2017. "Intimate partner violence and the overlap of perpetration and victimization: Because the influence of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse in childhood." Criminology and Criminal Justice Kinesthesia Publications. No. 46.

Roy, J. and Due south. Marcellus. 2019. "Homicide in Canada, 2018." Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Imperial Canadian Mounted Constabulary (RCMP). 2019. Intimate Partner Violence and Abuse. (accessed 25 February 2021).

Roughshod, L. 2021a. "Intimate partner violence: Experiences of women with disabilities in Canada, 2018." Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Savage, L. 2021b. "Intimate partner violence: Experiences of young women in Canada, 2018." Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Statistics Canada. 1993. "The violence confronting women survey." The Daily. November eighteen. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. eleven-001-E.

Widom, C. S., Czaja, Southward. J. and K. A. Dutton. 2008. "Childhood victimization and lifetime revictimization." Child Abuse & Neglect. Vol. 32. p. 785-796.

Widom, C.S., Czaja, Due south.J. and K.A. Dutton. 2014. "Child abuse and neglect and intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration: A prospective investigation." Child Corruption & Neglect. Vol. 38, no. 4. p. 650-663.

Women'south Shelters Canada. 2020. "Special consequence: The impact of COVID-nineteen on VAW shelters and transition houses." Shelter Voices.

World Health Organization. 2012. Understanding and Addressing Violence Against Women. (accessed 25 February 2021).

World Health Organization. 2017. Violence Confronting Women. (accessed viii January 2021).

Report a problem on this page

Is something not working? Is there data outdated? Can't find what you're looking for?

Please contact u.s. and let us know how we can help you lot.

Privacy notice

- Appointment modified:

Source: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2021001/article/00003-eng.htm

0 Response to "Women Comming From Domstic Viloent Siuoations Act When Dating Again"

Post a Comment